Medieval Layouts

Introduction

To better understand the historic buildings in Meldreth it is worthwhile considering what came before and how Medieval design traditions completely influenced house building in the Early Modern period. Buildings have been constructed from wood from time immemorial. Wood was widely available, its cost was low and, compared to stone, it was relatively easy to transport and to use.

Prior to the Norman invasion in 1066 the Anglo Saxons were building wooden-framed open long halls and it is reasonable to assume these were influenced by earlier Roman buildings.

The two oldest half-timbered buildings in Meldreth are Chiswick House and The Green Man in North End – both early to mid-1500s and therefore considered to be Early Modern. The remainder are predominantly 17th and 18th century. There is a caveat regarding Chiswick House in as much as it does contain a timber beam dated 1340 but this may have been taken from an earlier building and reused or, perhaps the inner core of the building is, in fact, Medieval.

The Open Long Hall

Our use of the word hall has somewhat grand connotations but in Old English pre-1150AD – a heall was simply “a roofed space”

In basic terms, long halls were three to four times longer than they were wide with a pitched roof. Internally they were open from wall to wall and from floor to roof.

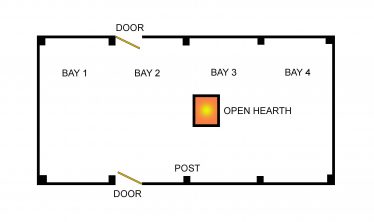

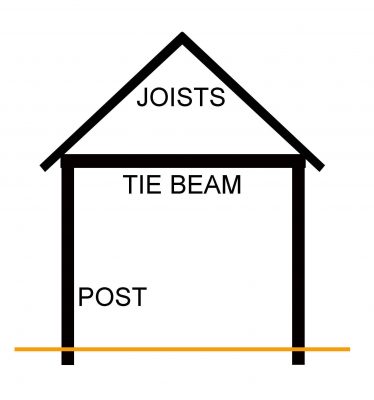

Vertical timber posts were set at or into the ground at regular intervals, joined width-ways at the highest point by a cross member or “tie beam” and topped by the roof joists. This created the basic box frame. The gaps between were filled with additional supporting timbers and panels made from what was the most abundant local solution – wattle and daub, lath and plaster, compacted mud, clunch, or clay bats. Roofs were thatched with straw or reed. Two entrance doors were set opposite each other and an open hearth fire was located centrally whilst avoiding a cross member to minimise the risk of setting the building alight.

You will see frequent reference to historic buildings being one, two, three, four, and even five bay.

A bay in architectural terms is the space between each upright and defined as “the distance between two supports in a building with a pitched roof”. It derives from old French bae – “hole” and the earlier Latin bado meaning “I am open.”

The plan example shown above has five posts per side creating four internal bays.

Medieval halls were the essence of communal living being home to the owner, his family, his workforce, and house servants. Kitchens in this period were typically housed in a separate building.

The Enclosed Long Hall

A significant change in house building appeared around 1300 when the open hall design and layout began to enclose internal bays with walls or screens to create separate rooms, or “chambers”, each with a specific function. Typically bay one – the “lower end” – was subdivided into two store rooms – the “pantry” and the “buttery” – neither of which required heating.

The pantry contained foodstuffs and derives its name from Old French paneterie – “bread”. The buttery, despite its title, has no connection with butter. Instead, the buttery was used for storing barrels or butts containing ales and wines. The name is derived from Latin buttis – a “cask” via the Old French bot – “bottle”. The use of the word continues into modern English as, for example, a water butt and possibly, but not certainly, the occupation of butler. It is proposed the butler was originally the servant in charge of that room and its management.

Bays two, three and four initially remained as an open hall. Bay four, where the owner dined, was often raised slightly to reflect his or her status but in due course it, too, would be partitioned for the benefit of the owner to create a private space. This chamber, at the “upper end”, is termed the “parlour” and the name derives from Old French parloir – “to speak”. Parlours descended from monastic use, wherein a room was set aside allowing monks of silent orders to converse.

Similarly, the walkway between the two entrance doors was screened off from the hall to become the “screens passage”.

Bays two and three remained as a communal space but in larger and higher status hall houses, above the parlour and accessed originally by a ladder, a floor was added to create a second private chamber called the “solar”.

Solar could be a reference to the sun – a warm room with a sunnier aspect – but just as likely is a corruption of the Latin word solus – “solo” or “alone” indicating a private chamber away from the daily movements in the open hall. There are further examples of houses with a chamber above the pantry and buttery, sometimes linked to the solar by a gallery. In time the solar may have been extended further over the open hall into what we would quickly recognise as today’s two storey house with a clearly defined upstairs and downstairs……

“A two storeyed house, with a hall, kitchen, chapel, and several chambers arranged around a courtyard within a moat”

Veseys Manor House in Meldreth as described in 1503

It was this typical three bay or “tri-partite” template of service area, living area, and private quarters that continued out of the Middle Ages and into the Modern era.

For further information, please see the following pages on our website:

- Building Evolution and Layout: Introduction and Overview

- The Modern Era: Black Death and the Great Rebuilding

No Comments

Add a comment about this page