Memories of Meldreth and the War

Introduction by Colin Newell

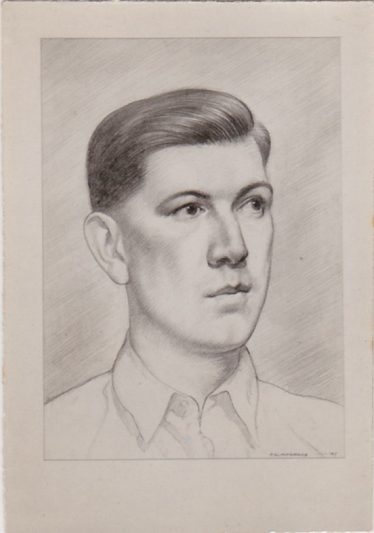

After my father died in 2013 we found, amongst his paperwork, a handwritten note about his early life in Meldreth – he lived in the village from 1932 until 1947. It was written on about a dozen lined pages from a spiral-bound notebook. The following is a transcript of the note, edited in places (see text in square brackets) for clarity and continuity. Several pictures have also been added.

Early Life

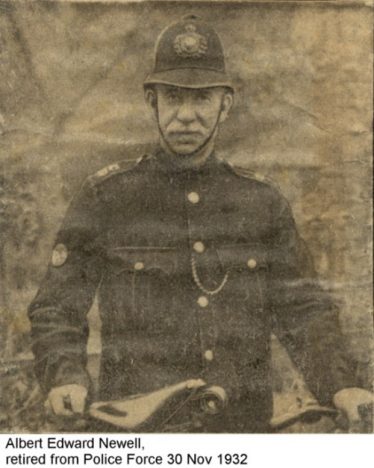

I was born in the village of Madingley, just outside Cambridge on 30th March 1924 to Albert Edward (‘Bert’) Newell and May nee Nodder. My father was a police constable and we lived in a police cottage.

My father was born on a farm [Hook’s Mill Farm in Tadlow, near Wrestlingworth, Bedfordshire]. He was one of 9 children and had a hard early life. He left school at 11, not by choice but by force of circumstances, the family being very poor, often having to resort to getting loaves of bread from the church, provided for the poor of the village. Sometimes he and his brothers put chicken-wire netting across the local stream to catch small fish by beating the water with sticks towards the netting.

I remember my father telling me a story that on one occasion he had to prepare a pony and trap to accompany his master on some visit or on business – quite a distance away. He had to be at the stable by 4.00am to groom and feed the pony, then polish the harness and brass work on the trap – more than 2 hrs work. When all was ready he and his master set off. It must have been a fair distance they had to go because just before reaching their destination his master produced a wicker basket from which he proceeded to eat his lunch. My father was very hungry but was not offered even a morsel. When they eventually arrived at their destination the boss left my father to ‘mind the horse’. It had a nosebag filled with oats for its lunch and my father had to steal some, rub them in his hands to remove the chaff, which he blew away, then ate the oats.

In spite of this hard early life he lived to age 92 – also in spite of smoking a pipe for most of his life.

Move to Meldreth

In late 1932, when I was 8 years old, my family and I moved to Meldreth. Dad had just retired from the police force and had, a year earlier, purchased Cornwall House and its orchard at Stone Lane, North End from his brother-in-law, George Nodder.

‘Uncle George’ had a new house built in Shepreth – the adjoining village – where he already owned an orchard.

School Days

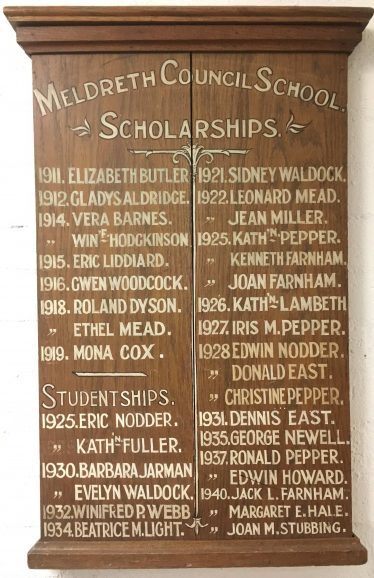

I then started at Meldreth Village School in December 1932. I went there until I was 11. The headmistress at this time was Miss Grace Butler. There were two other mistresses, sometimes three. Although my mother tried to ‘push’ my education, at that time I was not too willing a pupil.

I can remember the Jubilee sports (George V & Queen Mary) mainly for the astonishing performance my father showed in several of the events. I remember he won the 100 yds sprint followed by the slow bicycle race. He was a very fit man.

I used to either walk or cycle to school, about a mile each way. We sometimes played marbles on the way in the summer or had whipping tops. In the winter time many of us had hoops of steel approx. ¼ inch round section and 2 – 2½ ft diameter, which we trundled along the road with a wooden rod about 15 inches long, trying to keep it moving and also control its direction. Together with cycling this kept us fit.

I cannot remember any organised games at Meldreth School, just some very basic P.E. after morning prayers. I do remember several children contracting tuberculosis (TB), two of whom died. This was a very serious disease at the time and patients were sent away to sanatoriums to live with as much access to sunshine and fresh air as possible. The spread of TB was mostly through milk, most, if not all of which, was not pasteurised. Milk was sold from open churns, the amount being measured out in half-pint or pint scoops into all kinds of containers. Any farmer could sell his milk to anyone who would buy it. I do not know when the testing of dairy herds for TB began but there was, as far as I know, none in the Meldreth area in the early 1930s. Fortunately I did not like cold milk.

At the school leaving exam in 1935 I won a minor scholarship [from the Triggs Charity, which still exists] and went to the County High School for Boys in Hills Road, Cambridge.

Village Life

There was no piped water or sewerage in villages in those days. In Meldreth there were a number of natural springs from which we obtained drinking water. Our family had to fetch the drinking water in galvanised buckets from a spring about a quarter of a mile away. We paid one shilling a year for this water. Rainwater for washing and laundry was collected in tanks or pumped by hand from boreholes. Laundry was done by boiling the clothes in a “copper”. This was a large (2½ ft diameter) hemisphere of copper recessed into a square brick-built fireplace with chimney, which heated the wash-water in the ‘copper’ from underneath, using sticks wood and coal. The laundry was agitated with a copper dolly on a long wooden handle. The laundry, after boiling, was then put through the “mangle” – a wringer with large wooden rollers to squeeze out the water. The usual Monday “wash-day” took all morning.

Holidays and Family Visits

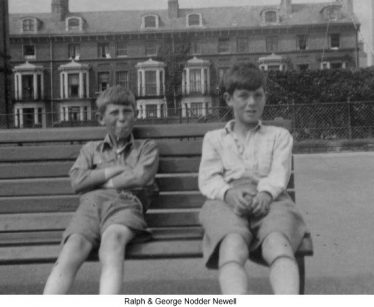

My father had a small police pension. As far as I can remember we at least had a holiday during the summer, either Mum and Dad took Ralph and I to Lowestoft for at least a week to a boarding house, or we went with my step-sister Bessie and her friend, always to the same boarding house. In those days we travelled by train.

We were fortunate to have family transport of a Triumph motorcycle with sidecar. My earliest recollection of this is of Ralph on my mother’s lap in the sidecar and me sitting on an old cushion tied to the motorcycle ‘carrier’ with my arms tightly clasped around my father’s waist. Such motorcycle trips were infrequent and never in the winter months. They were usually to visit two of my father’s brothers. One, Uncle Earn, lived somewhere near Bedford in a lovely little cottage for which he paid a yearly rent of one shilling. Another (Arthur) also lived near Bedford (or Wrestlingworth). I was terribly prone to travel sickness and only 2 or 3 miles on one of the old buses was sufficient to upset me. I dreaded travelling.

My favourite uncle, though, was Uncle Jack. He used to come by train from London to visit us, sometimes with his wife, Aunt Rose, and they would often stay at least one night. He was a tram driver and had both legs blown off when a ‘Doodle Bug’ bomb landed in the street he was driving along, completely demolishing the street. He survived and was fitted with artificial legs. A year or so later he and Aunt Rose were both killed when another bomb demolished their home. I do know that she was crushed under a large window lintel.

[NB For future family historians: The above is not completely correct. John ‘Jack’ Edgar Brockett Newell, a tramcar driver, was married to Frances nee Sanderson. He was killed outright on 5th Oct 1940 when driving his tramcar outside Goldsmith’s College, London. His wife, Frances lived until 1960. “Rose” was Jessie Rose nee Warren, wife of Wilf Newell, an elder brother of Jack, who worked as an inspector on the railways. Wilf and Rose lived in Dartford. Rose was killed by enemy action 20th April 1941 while Wilf died in 1950. Colin Newell April 2021]

Fruit Farming

My formative life revolved around fruit farming – mostly apples and plums. It was a hard life. There had been a national recession for several years and money was tight. My older stepbrother Bill also lived and worked at home. There was also Ralph, my younger brother by two years.

During the fruit-picking season the whole family had to ‘muck in’. There were a lot of plum trees of the variety “Pond’s Seedling”. The trees were very tall and usually bore very heavy crops to such an extent that branches sometimes fractured with the weight of the plums. On some occasions I was made to climb up very tall ladders held vertically by two men because the branches would not bear the weight of the fruit plus a man on a ladder. I was thus indoctrinated to heights at an early age.

Fruit was sent to Covent Garden market by goods train, so it had to be packed into round wicker baskets, covered with newspaper, which in turn was covered with straw, which was tied down. These were then loaded on to a pony cart and one of us, often myself, drove it to Shepreth station for the overnight journey to London. There it was auctioned. After transport charges and auctioneers commission, in times of glut little was left for us, sometimes just 6d for 20lbs of fruit.

I used to make some pocket money by picking up fallen apples for the local cider company. I remember I sometimes made a shilling a hundredweight. Two or three tons sometimes accumulated before they were collected and by this time many were rotten, but they were pressed for cider just the same. Times were hard then and money was scarce, but we were never hungry. We grew all our own vegetables and of course had plenty of fruit. My mother made jam and preserved a lot of soft fruit and plums. She also made pickles of all descriptions.

We kept a lot of chickens in the orchards, sold the eggs and also some table chickens and geese and ducks for the Christmas trade. From about the age of 12 I kept a sow and reared the piglets, one of which was fattened and kept for eating ourselves. There were no freezers in those days, so some of the pork was salted and made into bacon and ham. When the war came the rifle was also a very important tool in acquiring food.

Engineering Apprenticeship & the War Years

Just before the war began, and when I was aged 16, my father somehow arranged for me to be interviewed for an apprenticeship at Cambridge University Engineering Laboratory. I was offered a place and was tremendously excited by this as I and two or three of my friends had, since the age of nine or ten, messed around with motorcycles and soon learned how they worked and how to ride them. After harvest time was best for dirt-track racing around the stubble fields, springtime best around the orchards. To us petrol was expensive at just over a shilling a gallon, so we used to dilute it 50/50 with tractor fuel, obtained by various means and from various sources.

I was highly motivated and considered myself extremely lucky to have the opportunity to learn my skills at such a prestigious place. For the first year or so I cycled to and from Meldreth, some 10 miles, and had to be at work by 8 o’clock and rarely finished before 6pm. This was a long day and often, in winter, a tough ride in all weathers. I soon saved enough money to buy a roadworthy motorcycle which made life much easier. I enjoyed my work and made such good progress that I was soon having to do weekend work and overtime, further rapidly increasing my skills on an ever-increasing range of machinery. When I first began my training my wages were 11 shillings per week. On my 17th birthday I was given a rise of 4d per week. With overtime at time-and-a-half and Sundays at double time I was soon earning £1 per week.

Soon after I started my apprenticeship the 1939-45 war started. The war soon got tougher, and the Engineering Laboratories became even busier and night shifts were introduced. By 1943 I was working on high-precision projects – far in advance of what I would have been doing in a peacetime apprenticeship – and I was also being given considerable responsibility. Work was extremely interesting, and in many ways fun, despite being in the midst of a really terrible war. Many of the major cities in the southern half of the UK were in a terrible mess, with many people killed and injured from the bombings. The night skies were often filled with searchlight beams criss-crossing the heavens, and these were normally the only lights to be seen as all windows were blacked out and very few vehicles were on the roads – and those that were had to have covers on their headlamps allowing only three narrow slits of light to emerge.

Early in 1943 my younger brother, Ralph, was ‘called up’ and decided to join the Royal Navy. This made things harder at home for my father and my step-brother Bill. However, ‘call-ups’ were expected. I was, however, granted ‘Reserved Occupation’ status, as was everyone at the Engineering Lab. Also, every male of reasonable fitness had to join the Home Guard or VII Corps or Special Police and everyone was given instructions on how to keep a watchful eye for spies who, it has transpired since, were much more numerous than the general population believed. Large numbers of bombs with delayed action fuses were being dropped by the Luftwaffe and their fuses were only slowly being mastered by the bomb disposal squads – at great cost in lives lost. Years after the war, when secret files were released, it transpired that German spies were very efficient in keeping their masters informed and new designs were continually substituted.

The next great morale-breakers were the Flying Bombs – literally a 1,000lb bomb with wings and a tail-mounted RAM-jet thruster motor. Nicknamed the ‘Doodle Bug’, this was launched from a ramp on the Dutch or Belgian channel coast and set on a compass bearing. Its speed was fixed and it had a fuel cut-off device which operated at a pre-set point. London was the main target and because of its large area the range was easily calculated. These bombs exploded on surface impact and caused horrendous damage. Many passed over East Anglia flying towards targets in the Midlands at only one or two thousand feet, too low for anti-aircraft guns, and too fast for most of our fighters at the time. Very few were shot down. They were demoralising to Londoners as the Germans only had to keep a few going over at short intervals to keep them in their shelters. People soon learned to take not too much notice of them until the engine cut out. The spy network must have reported this back as a modification was soon devised whereby the flying bomb went into a turn before diving so that no-one had any idea where it would strike. This was a morale-breaker and a real success for the Germans.

The next such weapons were the V2 rockets. They were not as numerous as the Doodle Bugs nor as morale-sapping. This must have been because they could not be seen or heard approaching. They descended from the stratosphere at sonic speed and one ‘heard them coming’ only shortly after they had exploded. Their guidance system must have been somewhat crude as they seemed to land as often in the countryside as in built-up areas.

In general, unless some bombs, rockets or planes, whether friend or foe, caused incidents locally, one didn’t hear much. Information given out was kept to a minimum unless it was deemed to boost morale. However, Dad was recalled to police duty at the declaration of war and much information came through to us on the telephone, especially if it involved the Cambridge/Herts area. There were many aerodromes nearby, some fighter, some bomber, both RAF and USAF, so the skies were daily filled with planes either setting out or returning from operations or doing training ‘circuits and bumps’. There were often crashes in the area and sometimes shot-down enemy planes. There were many nights when the skies over East Anglia were full of Nazi bombers going to and returning from targets in the Midlands.

During the war period numerous bombs landed in the Meldreth area, but, astonishingly, not one did any damage. It seemed that most were just dumped because the enemy hadn’t reached its designated target or it was being pursued. Several, though, did give us more than a slight fright. One, a one thousand pounder, landed just in front of a parked car only a quarter of a mile from our home. It had screamer whistles on its fins and it scared me terribly because it seemed to be coming straight at our house. I hid in the stair cupboard. After the hole was examined by the Army Bomb Disposal people the car was towed away and a cordon put around the hole, but it was four years before it was eventually dug up and removed by the Army.

My personal near miss was on one brilliant, clear summer morning. I had arrived home from night shift at the Engineering Lab and just as I was about to walk into the house my father, who had received a telephone alert, pointed at a formation of German bombers approaching – a dozen or more. They were high but suddenly we saw a shower of bombs shining in the sunlight as they dropped, and my father shouted to take cover. I ran into the ‘tin shed’ – a corrugated iron outbuilding and jumped into the large wooden corn bin and shut the lid. Within seconds the explosions began, rapidly getting nearer, then one almighty one which seemed to lift me up. Then silence – apart from the drone of the bombers – no sign on anti-aircraft fire or of any of our own fighters. I was almost stifled by dust and had to open the lid of the bin, only to be confronted by the acrid smell of explosive. The bomb had impacted just 10 yards away and there was a sizable mound of chalk, perhaps 6 or 7 yards diameter and 6 feet high, uprooting one apple tree. There were in total three parallel rows of bombs some 5 or 6 miles long, not one of which had hit anything, neither road, railway or bridge. Again, it seems probable the bombers had been unable to penetrate the defences round London and had unloaded their bombs at random.

By this stage of the war, despite intensive bombing of some of our main industrial cities, the RAF had built up a large bomber force and Winston Churchill and the Government had ordered retaliation bombing of some German cities. This was carried out but at the cost of heavy losses on bombers and crews. Sometimes 60 or 70 planes were downed in a single night. It was soon discovered that the majority were being shot down by enemy night fighters coming up and shooting them from the underside, which our gunners were unable to cover. Consequently, a crash programme to design and install several prototype under-defence gun mounts was initiated, and the Cambridge Engineering Lab was one of the groups involved. This began a most exciting period of my wartime career, partly because I had, by this time, gained a lot of experience and was apparently considered quite a competent engineer.

We were allocated a RAF liaison officer, memorably named John de la Poer Beresford Preston, who seemed to have authority to get anything and to have access to almost anywhere. Through him we acquired two .50 calibre Browning heavy machine guns from one of the American bases. The design team then got busy designing mounts for these and within 2 or 3 weeks we had a prototype ready for testing. We were allocated a Stirling bomber as a test-bed. This had an escape door in the floor behind the bomb bays which was about 3 feet in diameter and just lifted out after unlatching. We mounted our gun on the edge of this and it was counterbalanced by the gunner sitting on a crude seat. He could cover a wide arc both rearwards and downwards. Belts of ammunition were fed down each side of the fuselage. We were flown over The Wash to test it and used many 1000s of rounds shooting at seagulls but never hitting one. The following month or two saw modifications and more testing until we were instructed to make and install them. This was done under great secrecy at Feltwell Aerodrome in Norfolk in a group of four Stirling bombers. We never learned how other development groups were faring, but we were told that ‘our’ four planes had returned safely from their first trip.

I was then allocated to a group developing a rear gun platform for Fleet Air Arm Barracudas – a torpedo carrying aircraft. By that time I had had several flights and was highly motivated by the work – working very late and often very long hours. I had, however, progressed from cycling to riding a motorbike. This was not the safest of transport during the winter. Roads were not gritted and there were frequent fogs. On one such foggy night I collided with a stationary army lorry. It was parked outside Harston Village Hall (then an army NAAFI canteen) and its only light was fixed to its rear axle. I could not have my motorbike light on as that just made visibility worse. Luckily because of the dense fog I was riding very slowly with my left foot in touch with the side of the road. However, I didn’t see the lorry and collided with it. I woke up in hospital with severe lacerations to my cheek and knee and right arm but nothing fractured.

Soon after this I bought my Aunt Lou’s [Louise Stearn nee Nodder] Morris 8 car and life became much easier. I was eligible for special petrol and/or coupons, but even so spent much effort scrounging extra coupons or petrol, even from RAF stations where I sometimes had to go. Their petrol was dyed red and it was an offence to use this in civilian cars. With Dad being a policeman I could not really risk being caught. However, it was a case of ‘needs must’ and it was possible to remove the red dye from the petrol with silica gel before putting it into the car.

The Engineering Lab was by now geared up mostly for armaments research and students practical work was kept to a minimum. We were now working night shifts on alternate fortnights and sometimes those shifts went up to 18 hours and 7 day weeks. In the fruit season I also had to help whenever I could, leaving very little time for any social life. I completely missed out on learning to dance and I have often regretted that.

Quite a lot of the projects we worked on at the Lab we had no idea what they were for. Everything was highly secret, and the War Office tried to ensure that component parts were made in different places with final assembly elsewhere. However, for some projects it was not possible to do that and one of these I worked on was trying to find the ideal shape of armour-piercing shells made from different kinds of alloy steels. These were up to 40mm in diameter, and I had to start working from blanks of the designated alloys using a special jig on the lathe to create the radii as per drawings supplied. I had previously made a test rig 15 or 20 feet high where these ‘shells’, fixed onto a predetermined weight, could be dropped onto a sample of armour plating and the penetration was very accurately measured. Some of the results astonished me as just a slight change in radius could cause greatly enhanced results. I remember an armaments inspector from Woolwich Arsenal made several visits to collect results and samples and he put great pressure on me to produce them more quickly. This applied to almost every project. However, everything was interesting and I no doubt had an apprenticeship second to none and also learnt twice what I would have from a peacetime progression.

Around the middle of the war I met my future wife, Hazel [Sims, daughter of Fred and Frances, living in Howard Road, Meldreth], but my time for courting was very limited. I can remember our scarce evening walks being constantly interrupted by Doodle-bugs flying over and enemy bombers likewise. Most of our own bomber force lined up into formations and left on their missions during early evenings. The whole of East Anglia was dotted with bomber and fighter stations, and there were searchlights everywhere. As the months passed the eastern half of England became virtually a huge military base. We didn’t know it then but this was of course part of the build-up for the June 1944 invasion of France.

One day I had to go to RAF Feltwell in Norfolk to help fit one of our prototype under-defence gun mounts into a Stirling bomber, as mentioned earlier. It was getting dark by the time we had completed our task and we set out to return to Cambridge. We got no further than the [air] station entrance and told no-one was allowed out. No reason was given but a WAAF officer came and took us to the sergeants’ mess and we were given a meal and drinks. Soon after midnight we were told we were free to go. Next morning it was announced that the first 1,000 bomber raid had been carried out on Hamburg. We were slowly gaining the upper hand over Germany, but sadly suffering heavy losses in aircraft and crews. Soon, though, large numbers of American aircraft and servicemen began to flood East Anglia and they began carrying out large daylight raids on Germany, escorted by fighters.

News of the horrendous destruction in London was suppressed to the public at first. However, Winston Churchill saw that morale was slipping and ordered similar bombing [of German] cities.

Because of damage inflicted on enemy airfields and rocket launching bases, heavy bombing of our cities virtually ceased. Attacks on England were the sneak raids by a few bombers on mainly coastal targets.

Roughly about this time, I can’t remember when precisely, I saw one of our first jet fighters – the Gloster Meteor – pass over. It was low, extremely fast (for the time) and frighteningly noisy. The designer of its turbo-jet engine, Frank Whittle, had been a student and spent several years at Cambridge Univ. Engineering Lab. developing his theories. He had moved out not long before I began my apprenticeship. A lot of his equipment was yet to be moved.

Postscript by Colin Newell

In 1946 George saw a job vacancy posted on the Engineering Department’s notice board. It was for an Engineer/Technician at a new Department of Genetics being created at the University of Edinburgh. He applied and got the job. This greatly upset his mother who “thought he was leaving the planet”. He moved to Edinburgh in mid-1947. Soon the post was split with the Animal Breeding Research Organisation (ABRO), later home to Dolly, the famous sheep. This arrangement remained for the whole of George’s career in Edinburgh, which lasted almost 40 years. He eventually retired in 1986, and he was awarded an MBE in that year’s Birthday Honours. As well as his ‘day’ job George was also well-known for constructing neurosurgical instruments, a ‘sideline’ that occupied many evenings and weekends in the 1960s and 70s.

George married Hazel in Cambridge in September 1951, some six years after they had become engaged. They had two children, Colin and Lynda. They moved from Edinburgh to Rotherham in 2008 to be nearer Lynda. George died in February 2013, just a few weeks after Hazel.

Comments about this page

Absolutely lovely piece Colin, very informative and brings home just how hard it was for our parents and grandparents.

Would love to talk to you about the Newell family, as I’m related to them as well from Tadlow branches

Add a comment about this page