Non-conformism in Seventeenth Century Meldreth

“In the first half of the seventeenth century religion continued to dominate people’s thinking just as it had done before the Reformation; it was an all-embracing force that shaped their ideas and gave meaning to their lives” (Howard Shaw, ‘The Levellers’, Longman, Green and Co., 1968). But this was also a period of increasing religious tension and resistance, particularly to ‘high church’ figures such as William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633-45, who tried to impose order and unity on the Church of England through a series of draconian reforms. The term ‘non-conformist’ came to describe any English Protestant who did not conform to the doctrine of the established Church. It appeared in the 1662 Act of Uniformity which required all ministers of religion to follow the ceremonies and rites set out in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. It also mandated that all Church of England ministers be ordained by a bishop, a demand which was deeply resented by the Puritans, a faction of the church which became prominent in the English Civil War, 1642-1651. As a result, more than 2,000 ministers were ejected from the established church. Non-conformists were also known as Dissenters (see Meldreth Church Rates – Local Police Constables Alleged to have Failed in their Duties, 1849 , elsewhere on this website, for a later example) and then, in the nineteenth century, as Free Churchmen when different non-conforming denominations joined together in the Free Church Federal Council.

W. M. Palmer in the ‘Puritan in Melbourn’, published in 1895, wrote that, following the Act of Uniformity, “many (non-conformists) cared little about forms and doctrine, and that they were preached to in a surplice and heard prayers read out of a book” but others lived out a stern form of Puritanism in their daily lives and “resolutely refused to go up to the altar rails to receive the sacrament and to have their infants baptised with the sign of the cross.” Nor were they short of “men of culture and ability to lead them in (their) narrow and thorny path.” One of these was Joseph Oddy, 1629-1687, Yorkshire-born and a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. An ordained minister, he was said to be an earnest and eloquent preacher who settled at Meldreth after being ejected from his college Fellowship. (Note: some sources refer to him ‘losing his living’ at Meldreth in 1660 but Palmer is clear that this is incorrect; Thomas Elton was Vicar of Meldreth from 1626 – 1666).

Interestingly, in Edward Venables’ ‘Life of John Bunyan‘, (2005, transcribed from the 1888 Walter Scott edition) there is reference to the famous writer and puritan preacher, best remembered as the author of ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’, having preached at Meldreth: “in some places, as at Meldreth and Yelden … the pulpits of the churches were opened to him; in other places the incumbents of the parishes were his bitterest enemies.” Bunyan, who came from Bedford, worked as a tinker before his conversion to Christianity and Dr. T. Smith, the then keeper of the University Library in Cambridge, denounced him because “he strove to mend souls as well as kettles and pans”!

In 1664, the passing of the Conventicle Act made it illegal for more than five people, not members of the family, to meet in any house for religious purposes, unless they followed prescribed Church of England services. Churchwardens were expected to report to the bishop anyone in their parishes who did not attend church or take the sacrament (receive Holy Communion). However, Palmer writes that “the churchwardens of Melbourn and Meldreth were very careless, or else disposed to be friendly to the Dissenters. For although in 1662-3 many people in the neighbouring villages were reported for refusing to take the sacrament, or to come to church, none were so reported here, the only complaint being against Edward Cook of Melbourn, for refusing to pay his rate of 1s 6d for the repair of Bassingbourn Church.”

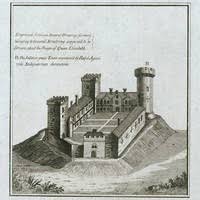

Apparently, the government was aware of of this lack of reporting and decided to take matters into its own hands. According to Palmer, it established “an elaborate system of spies in almost every county and town in England. It is from the report of one of them the we get the first mention of a separate meeting of Independents at Meldreth … (where) … there were concourses of many hundreds, both Independents and Baptists.” Joseph Oddy had an assistant named Thomas Lock who took turns to ride with him into neighbouring counties and to places such as Bedford and Hitchin “where he had many hearers”. Palmer speculates that “the reason for Oddy’s settling at Meldreth and making it a centre from which to work up the Independent cause in the neighbouring counties, was most likely that the feeling of independence was very strong in that village.” But things did not go well for Joseph Oddy who found himself thrown into prison at Cambridge Castle under the Conventicles Act. Evidently, while imprisoned at the Castle, he was let out by a friendly gaoler to preach at night.

Another leading figure in the non-conformist movement locally was Francis Holcroft (1633-1692). A Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, he was known for his courageous character and outspoken preaching. He was the first person to found churches on congregational principles. These held that a church should operate independently and autonomously and be able to determine its own affairs without having to submit to the decisions of a bishop or higher authority. Holcroft believed strongly that the structure of a church “should not be based on geographical boundaries but upon a company of Christian disciples, whether they lived in a particular parish or not.” (‘Convinced that these were God’s people’, A History of Melbourn United Reform Church’, R.W. Rooke, 1994). Known as ‘the Apostle of Cambridge’ (the words appear on his tombstone), he had been vicar of Bassingbourn but was removed from his ‘living’ there for preaching against the established Church. He also lost his position at Cambridge University which was linked with his position as vicar at Bassingbourn. He was a close associate of Joseph Oddy of Meldreth and was also imprisoned in Cambridge Castle, in 1663. They are buried together, along with a supporter, Henry Osland, at Oakington, on land next to the parish church cemetery but outside the church boundary.

According to Palmer’s account, non-conformity in Meldreth was not ended by Joseph Oddy’s time in prison. He tells how, in March 1665, several villagers were convicted at Cambridge Assizes for not taking the sacrament. Then, in 1669, from a report held in Lambeth Palace library, we learn that a meeting of Independents was held in Edward Simmons’ barn in Meldreth where there were at least a hundred regular attenders. Edward Simmons was a small farmer or labourer whose name appears in the Hearth Tax of 1674, when his house contained two fireplaces. There was particular government concern at the time over the activities of ‘Oliver’s soldiers’ – a reference to men who had fought with Cromwell (a devout Puritan) against the Royalists in battles at Marston Moor and Naseby, some of whom then became influential preachers. At the time (1669), Meldreth was thought to be the only meeting place for Independents in this part of Cambridgeshire with the exception of a smaller group in Orwell.

In 1672, the King issued a landmark ‘Declaration of Indulgence’ allowing all people to worship as their consciences dictated. Holcroft, Oddy and other non-conformists were released from prison but Oddy did not return to Meldreth, moving to Cottenham where he remained until his death in 1687. Following this Declaration anyone wanting to preach had to make written application to the Secretary of State providing their denomination and requesting that the building in which they wish to preach be licensed. Between May 1672 and March 1673, when Parliament forced the king to withdraw his Declaration, 47 premises and 27 preachers were licensed in Cambridgeshire. Amongst them , Palmer tells us, were the following: “1672, May 8th. The house of Widow Evans at Meldreth to be a Congregational Meeting Place; (also on that date). Thomas Lock to be a Congregational teacher in the house of Widow Evans; 1672, May 25th. Thomas Antrim to be a Congregational teacher at Meldreth; 1672, Sept. 30th. Thomas Austen to be a Congregational teacher at Meldreth.” Not much is known about the people mentioned in these licences but we are told “Widow Evans was in very poor circumstances, poor enough to be excused from payment of the hearth tax in 1671. She had been convicted at the Cambridge Assizes in 1665 for not coming to Church and her unpaid fines in 1671 amounted to £60”, a huge sum at the time.

The Victoria County History – Cambridgeshire tells us that there were 12 non-conformist families in Meldreth in 1676 (possibly an under-estimate due to fear of persecution) but the strength of the movement grew and many Dissenters were recorded by 1685. The passing of the Toleration Act of 1689 gave all non-conformists freedom of worship, in effect abandoning the idea of a ‘comprehensive Church of England’ and recognising that the best that could be achieved was the toleration of division. Non-conformists had to swear oaths of allegiance to the sovereign and were still disadvantaged (as were Roman Catholics) by not being able to hold political office. In Meldreth and Melbourn they established a meeting place and in 1694 the Congregational Ministry transferred from Meldreth to Melbourn, incorporating Bassingbourn and Great Chishill. The first minister was a strict Calvinist, John Nicholls, who continued in his post until 1735, a period of more than 40 years.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page