Not Quite But Nearly - Meldreth's Lost Waterway

Introduction

The year is 1840 and visitors from near and far have gathered at the British Queen Public House to partake in Master Nathan Driver’s most famed and propitious monthly test of knowledge. As the anticipation reaches its peak Master Driver stands, rings his starting bell and the first inquiry is made…

Which of the following is the odd one out, and why – the Red Planet, the Italian city of Venice, or the village of Meldreth?

Mistress Mortlock smiles and whispers in her husband’s ear. Nodding in agreement he writes their first answer …

Mars. There are no canals on Mars.

Wait, I hear you say. Why only Mars? There are surely no canals in Meldreth. Well, ‘tis true … but, for a brief moment in time, there very nearly was …

The First Plan

The year 1811 was marked by a newly published map describing a “Plan shewing the Course of the Proposed London and Cambridge Junction Canal from Bishops Stortford to Clay Hithe Sluice near Cambridge intended to Unite the Ports of London and Lynn….”

With equal enthusiasm the accompanying paperwork boldly claims “This Canal will connect the entire eastern-side of England south of Peterborough with London.”

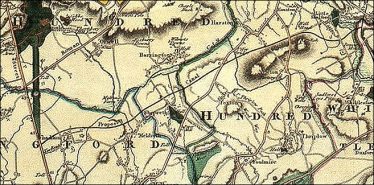

A further map provided reads “Blue Lines describe the Existing Navigations. Red Line describes the London and Cambridge Canal and Branch to Whaddon.”

Lord George Jackson Duckett

At first glance, to George Jackson, later Lord Duckett and the owner of the River Stort navigation, the building of a new canal linking East Anglia to Bishops Stortford and continuing onwards to the City of London made perfect business sense. Already half completed via the Rivers Lea and Stort, the land north to Cambridge was comparatively level requiring few significant engineering works … and the number of tolls he could charge would surely rise.

Lord Duckett’s vision was already ten years old when, in 1778, Robert Whitworth, a civil engineer to the Common Council of the City of London, at their bequest surveyed the route and confirmed the advantages. Whitworth proposed a line just over twenty-eight miles in length. Exiting Bishops Stortford, it would rise through fourteen locks to a tunnel at Elsenham and fall through thirty-seven more locks joining the River Cam a few hundred yards below Magdalen Bridge near the commercial wharves in Cambridge.

Meetings – where minutes were taken and hours were wasted

In 1781 a public meeting was called at the Crown, Great Chesterford by the Committee of the Thames and Canal Navigation of the City of London to consider the proposition and to assess both the desire for and the practicability of the new canal.

As a portend, perhaps, to the arguments and opposition and recriminations that haunted the project for the next thirty years, there was an immediate confusion over who had actually called the meeting. With many refusing to appoint a chairman until the confusion was resolved the meeting duly dissolved.

Seven years later the proposal was revived. Alderman Richard Clark of London chaired a further two better organised meetings at Great Chesterford wherein the invited noblemen, gentlemen and others were asked if they would back a proposal to further investigate the original proposal.

Not everyone in attendance was happy. The Corporation of the Bedford Level promised to continue their objection. To them the plans were promising no public good, but threatening much injury to the Fen-country … and that the City of London had interfered where they had no property for which Alderman Clark did apologise observing they were ready to unite in the service of the general advantage.

Amongst those in favour also present were John Montagu, Lord Sandwich of Hinchingbrooke near Huntingdon and local to Meldreth landowner and politician Sir Philip Yorke, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke. Both would continue to further their interest in and support for the project.

The most vocal private dissenter in the room was Lord Braybrooke of Audley End who considered the encroachment on his land entirely unacceptable. Other attendees from Saffron Walden wanting to further the town’s fortunes made no secret of the fact they were particularly unhappy with Lord Braybrooke objecting, with the conduct of these inferior beings being described as indefensible and an insult to their noble neighbour.

Being of the opinion that he had done far more for Saffron Walden than it had done for him, and making no secret of his displeasure, Lord Braybrooke retaliated by banning the same townsfolk from his land where previously they had been allowed to enter and hunt for game.

Aided and abetted by his friends in the Bedford Level Corporation, an amendment to route the canal behind his property was met with an equal lack of enthusiasm.

Regardless, of the five hundred attendees at the second meeting four hundred and eighty passed the motion and a public dinner was afterwards enjoyed by all.

Within a year a revised proposal was made to re-route the canal from near Saffron Walden to the Brandon River, but with additional branches to Cambridge and Burwell. Further connections would then be made to Ely and more to Huntingdon, Bedford, Northampton, and Lincoln. At an estimated cost of £175,000 both local and London-based interests supported the deviation but it also drew the opposition of the Cam Conservators, the University, mill owners on the Cam, and several more landed gentries whose property and views would be disrupted.

More meetings took place. Some shares began to be sold to adventurers. Solicitors were appointed and endless documentation was produced. More letters for and against the new canal were written but all progress slowly ground to a halt.

John Rennie

It was twenty years later that a new line was surveyed under the supervision of John Rennie. An acclaimed Scottish civil engineer, Rennie’s London-based firm specialised in large infrastructure projects. Amongst many important landmarks, he is best remembered for his design of the London Bridge which now resides in Arizona.

Having considered two alternative routes through either Barkway or Hitchin he returned to the original proposal but elected to extend the canal beyond Cambridge to join the Cam further downstream at Clayhithe, near Waterbeach; and add the branch from Sawston parish to Whaddon. As originally intended the Whaddon branch was to continue to Shefford where it would join the River Great Ouse, but to save money the decision was made to proceed no further than Ermine Street.

Nevertheless, this was still to the benefit of Sir Philip Yorke since it was on his land where the canal would cross Meldreth Holm Brook near Whaddon and would terminate at the southern edge of his country estate, Wimpole Hall.

Parliamentary Approval

Armed with Rennie’s new plan a Bill was introduced into Parliament in 1811. Opposed by the Bedford Level Corporation it was thrown out at committee stage. Re-introduced the same year, the Bill was passed receiving Royal Assent in 1812 but with a host of clauses to protect Hobson’s Conduit – Cambridge’s primary water supply, the tolls and rights of the Cam Conservators, and the estates of landowners who continued to complain bitterly about works invading their property.

Starting at the wharves in Bishops Stortford the new canal would pass Stansted Mountfitchet, Elsenham, Newport, Saffron Walden, Great Chesterford, Duxford, Whittlesford, Great Shelford, Trumpington, Cherry Hinton, Fen Ditton, and Horningsea. Between five and six feet deep the canal’s breadth would be forty-four feet at its narrowest and forty-eight feet at its widest.

On the main line there were now to be three tunnels – one over a mile long – and fifty-two locks. On the branch to Whaddon there were to be no locks but this was amended to thirteen locks if ever extended beyond Ermine Street.

The Whaddon Branch

Starting just south of Great Shelford the branch swings below Little Shelford before crossing the old London Road and Newton Road at Harston. Closely following the line of today’s railway line, it then cuts across the A10 main road just beyond the Foxton level crossing. Passing over the River Shep it meets the Barrington Road at the site of Shepreth railway station before running a short distance parallel with the lane leading to North End in Meldreth. Next step is the Guilden Brook and then the Malton Road just outside the village. Crossing the fields, it swings right touching what is now the edge of the Etex (Eternit) site and then left to the field opposite Whaddon church before terminating at Ermine Street.

Keen observers will note Rennie’s surveyed route between Whaddon and Shepreth is the same as the recently proposed, and now rejected, railway line linking Cambridge and Bedford.

William Jessop – the Second Plan

Lord Duckett was not the only person expressing a desire to link London and Cambridge by canal.

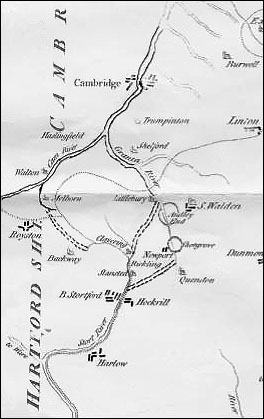

If William Jessop, another noted civil engineer and associate of John Rennie, had progressed his plan the Rivers Stort and Cam would be connected long before reaching Cambridge. Putting pen to paper in 1785 Jessop published his Treatise on Inland Navigation illustrated with a plan delineating the course of an intended Navigable Canal from London to Norwich to Lynn.

In it he wrote the following remarkable assessment:

I would cleanse, widen, and deepen the river Stort, from Bishop Stortford to its very source, between Mesden (Meesden) and Barkway; and to do the same from Cambridge up the river Cam, by Walton (Malton) and Meldrith, even up to the source at Milbourn (Melbourn): from which two heads (Bury springs) I would make a circuitous cut to come near the town of Royston….

His sense of place may have been slightly vague since not only does his map show the Mel connecting to the Stort near Barkway but also the Stort at Clavering connecting to the Cam, or Granta, at Littlebury. The Royston cut disappears off the page but is presumably heading in the direction of the Cam’s source at Ashwell.

Had Jessop’s plan been adopted, a Sunday walk in Meldreth would be a very different affair today. From Flambards Bridge you may imagine turning to the right and strolling along the towpath to Melbourn Bury and beyond. Turning left will take you along the towpath through Melwood to the church and across the fields to the River Cam. At any point you may rest, converse with the anglers, and watch the pleasure boats go drifting by.

Where did it all go wrong?

Engineer Robert Whitworth had done exactly what was asked of him and sensibly suggested a route that was easiest to build. What he failed to realise was his route still passed through the Audley End estate of the late Lord Braybrooke whose vision for his estate did not include it being crossed by a canal having invested, he claimed, £100,000 in landscaping and replanting.

Never resolved, Lord Braybrooke’s death undoubtedly reduced resistance to Lord Duckett’s grand plan. With Parliamentary approval of his proposal, the 1812 Act stipulated Lord Duckett and his associates were permitted to raise a maximum of £570,000 in shares of £100 each and should this prove insufficient they could raise a further £300,000 amongst themselves. However, they may not proceed until £425,450 had been raised within a time limit of four years.

“The Company of Proprietors of the London and Cambridge Junction Canal” was duly formed but for the supporters of the plan the closing years of the Napoleonic Wars proved not the best for financial investment.

Amendments to the route including the proper aqueducts and other works, from the said canal at Great Shelford to Whaddon were forcing the costs ever higher and estimates now climbed to more than £540,000. Still the Company was forbidden to make any works at Audley End and other country residences, nor should they remove water from any natural waterways necessitating the construction of five supply reservoirs along the route and the installation of steam pumps to move water from the reservoirs to higher ground. The public subscription managed only to raise a little over £121,000 and the project began to stall.

Not to be outdone, in 1814, and now in his late eighties, Lord Duckett went back to Parliament and obtained a further Act to permit the start of construction of the length between Clayhithe and Saffron Walden, and the Whaddon branch, using the money raised but by now it was all too little too late. Both financial and political objection and counter-objection had become the order of the day …

Saffron Walden demanded a deviation of the route to the town wherein a wharf be built for their own use to create a distribution point, but the maltsters and warehouse owners at Bishops Stortford who controlled the movement of corn into London, and grown rich on the proceeds, objected on the basis that their monopoly would be curtailed. It wasn’t just corn distribution that concerned them. There were seeds, butter, chalk, limestone, oziers, billet-wood, sedge, wares, groceries, fruits, vegetables, cattle, timber, deals, planks, and coals. A huge amount of trade was at stake.

Proponents produced elaborate costings to show moving one barge of forty tons would cost £300 whereas the same weight of goods would require eight wagons and sixty-four horses costing £4000. The owners of horse drawn wagons said nonsense and complained their livelihood would be taken away. Those that grew grain to feed the horses complained their livelihoods would also suffer. Dismissed as having very trifling objections so, too, were those who put up resistance to their houses being knocked down in Great Shelford where the canal would run.

Contesting the claim of lower canal freight costings, the ship owners of Lynn, now threatened with unemployment, produced their own figures to show sending the same insured goods by boat round the coast to the Thames estuary would actually cost less. Another expert stated the charge would be no more and no less than carriage overland but would have to be similar otherwise no investor would ever recoup their share value. He also noted a lack of water in the canal in summer and ice in winter would hamper the movement of barges.

Detractors further pointed out that shallow draught barges whilst perfectly at home on the canal, those that proceeded onwards to Lynn would no longer be safe to use once they met the fast-moving tidal waters. Other engineers stated the building costs greatly under-estimated the porosity of the chalk through which the canal had to be cut, and the number of embankments and cuttings were equally under-estimated.

Also facing a fall in revenue, those controlling the turnpike roads filed their objections. Farmers noted delivering their produce to Chesterford and paying barge fees would actually save no more money than transporting their goods by wagon directly to Bishops Stortford whilst the owners of land either side of the canal banks were promised free freight passage… unless they needed to pass a lock for which they had to pay.

Letters of support and letters of dissent arrived in newspaper offices, monies were calculated and recalculated, dissertations were written, and, to the tune of the Star-Spangled Banner, a protest song was composed and published declaring These sly canal-mongers should there be defeated.

One author concluded a project originating in speculation alone would produce great loss to the subscribers, great injury to many individuals, a considerable waste of very valuable land, and no benefit to the public.

Another cuttingly asked, Is there any example of a Proposal to raise such a large sum with the prospect of so trifling a Profit?

The End of the Line

In response to the hostility the Corporation reaffirmed reduced rates of conveyance, safety and facility in conveyance to the most advantageous markets, the encouragement of farmers crippled by the enormous expense of land carriage, savings on keeping horses, release of land where food could be grown for men and not horses, savings through not repairing turnpike roads, a reduction of waste, and supplying goods at lower prices for the alleviation of the hardships of the poor.

It made no difference. Despite all the efforts of those in favour, the project simply ran out of steam. There was no dramatic collapse. The division of opinion, the passage of time, and the reluctance to invest meant the required monies were never raised. One by one the key proponents passed away and others moved their attention onto new projects. With hindsight a later commenter wisely noted:

When first proposed canals were the height of technical and commercial achievement but in reality, what could have been built would have been put out of business by the arrival of the railway within a decade or two and never recouped its investment…

Conclusion

For us looking back at these few decades it highlights not just the level of engineering expertise involved but the power and influence the knights of the realm had at both local and national level. It exposes the differences of opinion amongst themselves and the class war they were prepared to enter into with ordinary citizens. The sheer level of bureaucracy is overwhelming and only equalled by the huge amount of traded goods crossing from county to county. Existing Corporations did not hesitate to protect their vested interests against those of newly formed Corporations and individual towns were equally happy to put their local concerns ahead of those of their neighbours.

Other than the paper trail it would seem there are no other reminders of the project. There is, however, one poignant reference still to be seen. On a modern river route map, between Clayhithe Bridge Road and Bottisham Lock and Sluice there is still a marker. It simply reads:

London & Cambridge Junction Canal

Never built

No Comments

Add a comment about this page